In addition to their incredible work off-campus, our PAIA students are also engaged with moving the debate forward on-campus. As such, they have worked to develop articles focused on a dataset of their choosing.

The Indonesian National Health Insurance Policy: An Attempt to Ensure Equitable Access to Healthcare

Prepared by Nazla Mariza, M.A.

Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow

Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University

The Government of Indonesia launched a national health insurance program (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, or JKN), in early January 2014 as a form of commitment to ensure the Indonesian people’s access to health services. This political commitment was initiated during the leadership of Susilo Bambang Yudhono through the issuance of Law Number 24 of 2011 on the Social Security Administering Body (Badan Penyelenggaran Jaminan Sosial) or BPJS. BPJS is a government agency with the mandate to manage two National Social Security programs: BPJS Kesehatan (Social Security Administrator for Health) and BPJS Ketenagakerjaan (Social Security Administrator for Employment). Prior to the establishment of BPJS, multiple government agencies managed five different national social security programs for specific groups: Aspen (health insurance for civil servants), Taspen (pension Insurance for civil servants), Jamsostek (social insurance for private sector workers), Asabri (health insurance for armed forces personnel), and Jamskesmas (health insurance for the poor and near-poor). Governments at the provincial and district level also had authority to provide Jamkesda (a local version of Jamkesmas) to their local citizens. After the establishment of BPJS, all social security programs were integrated into one system and expanded to serve the entire Indonesian population.

This post focuses on the ambitious and problematic JKN Program managed by BPJS Kesehatan (Social Security Administrator for Health). I point out some implications which emerge after JKN’s four-year implementation program and whether it manages to achieve the policy goal of providing equitable access to health services for all citizens and residents. Further research is needed to collect more valid data and to generate recommendations for policy improvement.

Universal health coverage

As can be seen, JKN is available for all Indonesians. This premise drives BPJS Kesehatan to provide equal health insurance for all citizens instead of targeting specific groups. This scheme leaves a big question as to whether equal input can achieve equal outcome, or in other words, equitable access to health services for all people.

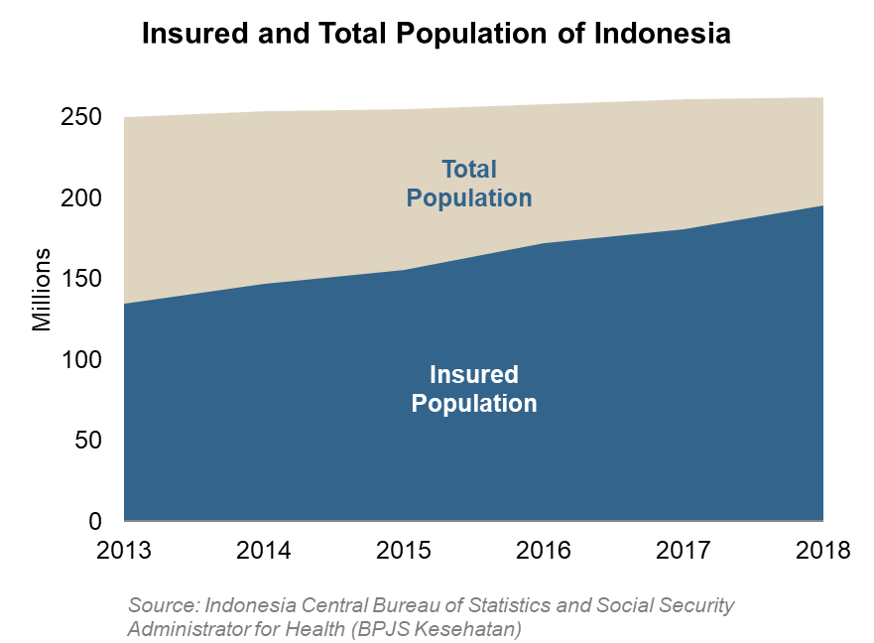

One of BPJS Kesehatan’s main targets is to achieve “universal health coverage,” which means all citizens and residents of Indonesia have to be registered in JKN. Before JKN was launched, only 54% of Indonesians were covered by public insurance through various schemes (Central Agency on Statistics, 2013). By April 1, 2018, around 195 million out of 262 million people, or about 74% of the total population were registered in JKN (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2017). This 20% increase within four years is one of the visible achievements of JKN program.

Nevertheless, the number of JKN registered participants only represents one key indicator of BPJS Kesehatan performance. Behind this sharp increase, the JKN program, in fact, triggers various problems.

The provision of health insurance to all citizens raised expectations, especially for those living in small islands and remote areas where public services are lacking. The nonexistence of proper health services in these areas complicated the promotion of JKN. Logically, being insured does not always equal to having access to health care. Those who are insured through JKN do not always have the access to use the claim.

Imbalanced access to health facilities

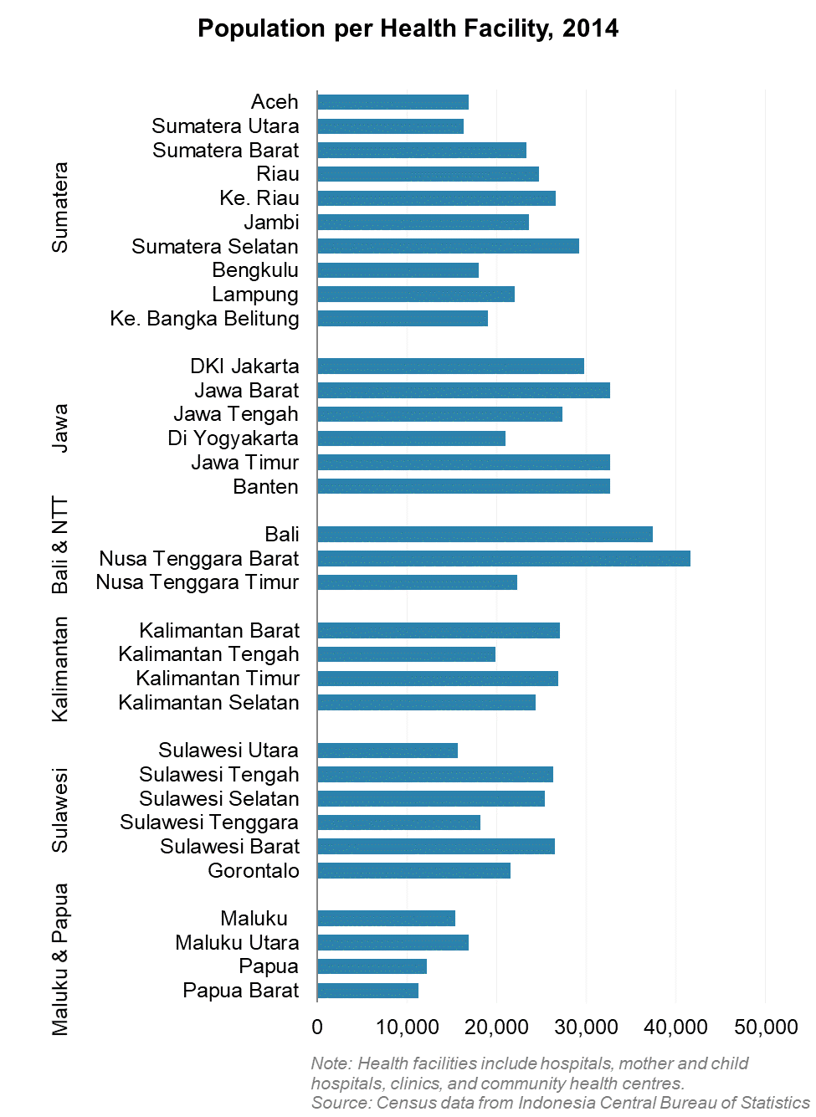

Classical problems regarding the imbalance of distribution of health facilities and medical professionals in Indonesia make the JKN program inefficient, especially in remote areas where the health facilities are rare. Yet those are the areas where the poorest population mostly lives. This constraint contradicts the promise of JKN. The program is inoperative in those areas and insurers are frustrated.

According to Indonesian Central Agency on Statistics (BPS), there are 154,379 total health care facilities in the 33 provinces in Indonesia, including public and private hospitals, clinics, community health centers, and pharmacies. Compared to the Indonesian population of 262 million people, these facilities are overburdened. For example, Kepulauan Bangka Belitung, with 1,373 million people, has 389 health facilities. That means 3,529 people need to access one health facility. Moreover, most of these facilities have a small capacity of only one or two doctors. For comparison, West Java has 6,349 health facilities and 46 million people. This is equal to one facility for about 7,245 people. There are 110,720 registered doctors in Indonesia (Indonesian Doctor Association, 2016) which means one doctor serves 2,270 patients.

In addition, the facilities are not equally distributed throughout the country. Health facilities and doctors are mostly concentrated in big cities. Despite that, the public hospitals in big cities are always overwhelmed especially after the implementation of the JKN program. Furthermore, not all health care providers participate in the JKN program, particularly privately-owned providers. Up to 2018,only 65% of hospitals in Indonesia have implemented the JKN program.[1] Thus, lots of JKN patients are stacked in partner hospitals. This condition is worsened by the large number of JKN patients referred from community health services, which mostly have limited capacity. This stacking of JKN patients leads to slow response times and long waits.

Consequently, those who can afford private insurance never use JKN services although they are registered.[2] Even though this indicates lack of trust in JKN services, this could be a positive signal for BPJS Kesehatan, as they can save extra money to cover the claims from the remaining JKN patients.

Service providers can discriminate against JKN patients

BPJS Kesehatan receives complaints from JKN patients who experience discriminatory treatment during admission. They complain about uncertain delays before receiving healthcare treatment.[3] This delay can potentially harm patients in emergency situations that need to undergo immediate surgery. Some cases show that the patients have to wait on the availability of an inpatient room and surgery room unless they are willing to pay additional costs to access first class service.[4] This certainly affects JKN participants, especially the poor.

Similarly, there are problems with the provision of medicines for JKN patients. The abundance of JKN patients is not matched by an adequate supply of medicine. Patients seeking drugs often have to pay for them out of their own pockets. A study conducted by the Center for Economic and Health Studies of the University of Indonesia showed that 42% of JKN patient respondents still incur private costs to buy drugs and 31% of respondents are inpatient in the partner hospitals.[5]

Ineffective cooperation with public and private hospitals

To reach out to wider audiences, BPJS Kesehatan expanded the partnership with public and private hospitals. Partner hospitals mostly have to adjust their policy according to their agreement with BPJS Kesehatan, and most of the time this is not convenient for the hospitals. Partner hospitals also often complained about the frequent changes of BPJS Kesehatan policy including the insurance rates and coverage. The socialization of the policy to partner hospitals has been weak particularly to hospitals in the remote and outer regions. Public hospitals have no choice but to follow the regulation as it is a mandatory program. Although it is not mandatory for private hospitals, they will miss out, if they do not follow suit. There have been sporadic protests from various health care providers, particularly specialists on the JKN standard rate and payment system.[6] JKN apply lower medical service rate which this has been a big issue for partner hospitals as well as the doctors who suffer from the agreement.[7] There are some protests from the Indonesian Doctor Association about the detrimental impact of the BPJS Kesehatan program to doctors working in JKN partner hospitals.[8]

Another factor that creates a reluctant response from hospitals toward JKN patients is the slow payment from BPJS Kesehatan.[9] The chairman of the Indonesian Association of Regional Hospitals and Representatives of Indonesian Hospital Association criticized the poor performance of BPJS Kesehatan in disbursing claim payment to health partner providers particularly at the district level. BPJS Health admits there is a delay of claim payment to partner hospitals due to some reasons. These include budget constraints, administrative incompleteness and unmatched value between the amount of contributions received and the cost of health services paid.[10]

These debts automatically impact the way hospitals provide services to JKN patients.

Financial deficit and burden to the state budget

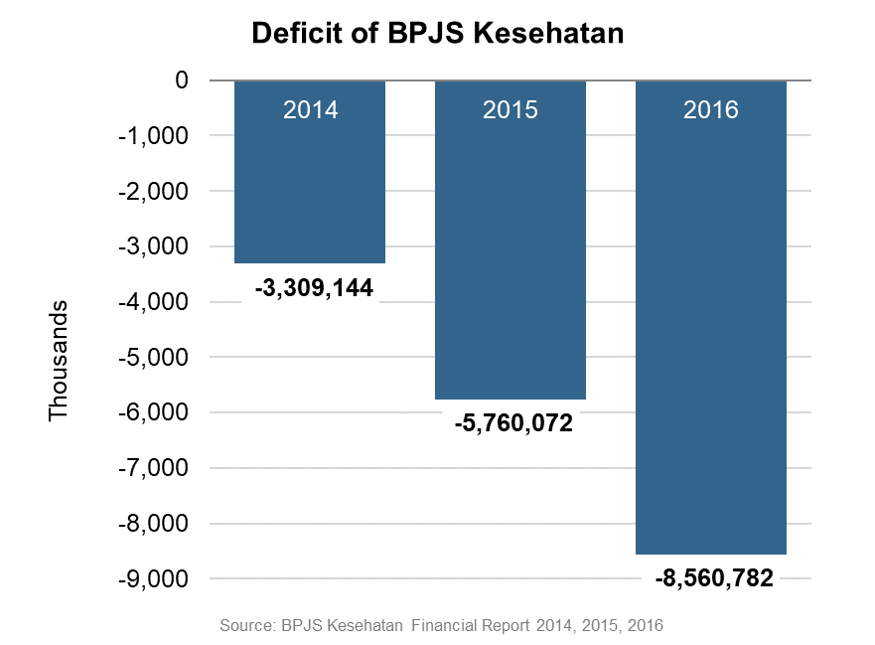

As mentioned, one of the reasons for delayed payment to partner hospitals is budget constraints. As a matter of fact, since its establishment in 2014, BPJS Kesehatan continues to experience deficits. The initial loss was 3.3 billion rupiah in 2014, then it increased to 5.7 billion rupiah in 2015 and reached 8.5 trillion rupiah in 2016 (around USD 653 million). Exploration of the reason behind this deficit is subject to further research.

At this point, it is understood that the JKN is a high-cost program. With minimum contribution of IDR 2,300 per month (around USD 1.7) up to IDR 80,000 / month (around USD 6.1), a participant can claim unlimited medical services even in the first month of joining the program. For comparison, China, a more developed country than Indonesia, implemented national health insurance with limited coverage in the early years. Then it grew gradually along with the increased capacity of their economy. An extreme example illustrating the high cost of JKN program is the cost of kidney failure patients per year, which can reach 2.6 trillion rupiah (around USD 200 million) as reported by BPJS Kesehatan in 2016. Furthermore, some of those insured do not regularly pay their insurance premium after enjoying the medical services. As reported, 10 million out of 181 million people failed to pay insurance premium in September 2017.[11] This creates a big potential burden on the institution and government budget.

One more issue to consider is that the Government of Indonesia provides subsidies for the poor to join JKN. Each year, the government increases the number of these beneficiaries, which represents an additional burden to the government budget. As illustration, the government subsidized 86.4 million JKN participants in 2015. This number increased to 92.4 million in 2016.[12] Up to mid-2017, around 62% of JKN insurers are subsidized by national budget (52%) and regional budget (10%).[13] Not surprisingly, the state budget for health sector increased from 3.5% in 2015 to 5% in 2016.[14]

The JKN subsidy is, undoubtedly, important for the poor. Nevertheless, it is also important to create a balanced and realistic subsidy scheme. Otherwise, BPJS Kesehatan may be discontinued in the future if the deficit continues.

Fraud Potential

The BPJS Kesehatan monitoring system seems very loose. Fraud often occur as reported by Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW), and the fraud trend is increasing. Within the period of 2010 through 2016 in 15 provinces, ICW found at least 49 cases of fraud conducted by patients, health care providers and local government officials. ICW discloses such fraud, for example, in the case of marking up medical service cost, manipulating the number of JKN registered and drug specification.[15]

Next Steps

The Indonesian government commitment in JKN program is a huge step toward to universal health coverage, although the implementation remains challenging. On one hand, JKN has succeeded in reaching out to Indonesian citizens in a very short time. A 20 percentage point increase in the insured population within 4 years is an outstanding achievement. This is a positive contrast compared to health insurance schemes previously implemented in Indonesia. However, unlimited health coverage with a very small individual premium makes BPJS Kesehatan struggle with budget deficit. In terms of partnership, BPJS Kesehatan also has successfully expanded cooperation with public and private health providers. Despite this, there are some defects in the quality of cooperation and equal distribution of JKN partners among regions.

Given this fact, there is work to be done to ensure equitable health care access for all Indonesians. Extra attention should be given to improve JKN program implementation, monitoring, transparency, partnerships with health care providers, and to prevent budget deficits. According to Professor of the Faculty of Public Health University of Indonesia, Hasbullah Thabrany, the auspices of the JKN program depend on the adequacy of funds, the quality of good and equitable health services, and the compliance of program participants to pay dues.[16] Without significant improvements, the program could face bankruptcy and cannot be sustained for a long period.

[1] http://industri.bisnis.com/read/20180212/12/737659/keterlibatan-rs-swasta-di-bpjs-kesehatan-meningkat

[2] https://www.indonesia-investments.com/id/news/todays-headlines/70-of-the-indonesian-population-joins-universal-healthcare-program/item8209

[3] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/a-country-of-a-quarter-billion-people-seeks-to-provide-free-health-care-for-all/2016/05/18/f36bf7b2-1b93-11e6-82c2-a7dcb313287d_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6affe7723c8a

[4] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/a-country-of-a-quarter-billion-people-seeks-to-provide-free-health-care-for-all/2016/05/18/f36bf7b2-1b93-11e6-82c2-a7dcb313287d_story.html?utm_term=.4d2559065a01

[5] http://www.idionline.org/berita/ketersediaan-obat-untuk-pasien-jkn-kurang-terjamin/

[6] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23288604.2015.1020642

[7] https://www.indonesia-investments.com/id/news/todays-headlines/70-of-the-indonesian-population-joins-universal-healthcare-program/item8209

[8] http://m.mediaindonesia.com/read/detail/157840-idi-jkn-sarat-masalah-yang-tak-kunjung-tuntas-dibenahi

[9] https://bisnis.tempo.co/read/1060426/rs-swasta-keluhkan-pembayaran-klaim-bpjs-kesehatan-sering-telat

[10] http://www.koran-jakarta.com/bpjs-kesehatan-lambat-bayar-klaim–pelayanan-mitra-memburuk/

[11] https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-42138297

[12] http://nasional.kontan.co.id/news/peserta-bpjs-kesehatan-subsidi-negara-bertambah

[13] https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2017/05/26/separuh-peserta-bpjs-kesehatan-dibiayai-abpn

[14] http://www.kebijakankesehatanindonesia.net/25-berita/berita/2398-anggaran-kesehatan-naik

[15] https://news.detik.com/berita/3643405/icw-temukan-49-kecurangan-terkait-jaminan-kesehatan-di-15-provinsi

[16] http://koran-sindo.com/page/news/2017-06-04/0/21/Setumpuk_PR_BPJS_Kesehatan_Capai_Target_Pelayanan_100_